Great Salt Lake has tremendous importance as habitat for shorebirds. Forty-two species of shorebirds have been confirmed there. On May 21, 2021, Utah Governor Cox declared 2021 the “Year of the Shorebird” in Utah. In celebration, each month for the rest of the year, longtime shorebird enthusiasts Ella Sorensen and Max Malmquist will highlight some of the lesser-known shorebird species that typically do not receive as much attention as the boldly patterned American Avocets and Black-necked Stilts.

“Everything moves in constant motion. Only nothingness ever stands still. Transition is all there is.”

—From Seductive Beauty of Great Sat Lake: Images of a Lake Unknown, by Ella Sorensen

Wetlands with their adjacent uplands are charming lands, special places on Earth where nature has opened wide its portals to bestow its richest concentration of vigor and energized movement.

Here, nature has created a fabric of interwoven strands of moving parts. Everything is changing, coming and going, morphing, flowing, shifting place or position, growing or decaying, birthing or dying, rising or falling. With such prolific movement at a single site, one could expect bedlam, collisions, crashes, and misalignments, but nature has fashioned a magnificent masterpiece where each moving entity has a niche, a space of its own to meet its unique life requirements as it intermingles in the harmonious synchronization of the whole.

Sometimes motion is ostensive. Leaves and branches sway and rustle with the wind and restive unfrozen waters never for a moment stand still. Birds and insects fly, crawl, or scurry about in daily activities, vibrantly adding lively animation to the scene. Snakes slither, jackrabbits hop a jagged erratic path, rodents gnaw, and coyotes hoist their snouts, flare open their jaws, and howl. But sometimes the movement of a marsh is slow, such a mismatch to the speed of human perception that it appears motionless, totally devoid of movement. A dormant seed swells, sprouts, puts forth stems and leaves, blossoms, fruits, and then perishes, leaving behind another seed that begins the moving cycle of life once again. Movement when neither fast nor quick requires the added element of passing time for humans to detect.

Every spring and fall, a master of migratory movement enters the intense localized swirl of activity in Great Salt Lake wetlands. The Pectoral Sandpiper is “motion on a trajectory.” Planets have predictable repeating orbits and millions of shorebirds make reoccurring biannual voyages of varying distances up and down the hemisphere as they make their rhythmic passage from breeding to wintering grounds then back again.

The Pectoral Sandpiper, with annual flights of up to 19,000 miles, ranks (along with the more familiar Arctic Tern) among the world’s superstars of long-distance migration.

Each spring, shorebirds wintering throughout the entire southern hemisphere begin their journeys northward. Each species finalizes its flight, settling out of the sky along the various latitudes into distinct ancestral nesting areas that provide suitable habitat.

When winter touches a given habitat it spawns conditions hostile to shorebird occurrence and reproduction. Then spring—marching northward up the continent through natural processes like warming temperatures, snow retreating to unveil the ground, plentiful invertebrates becoming accessible—reverts conditions back to suitable productive habitat. When the scene has been properly set and in timing with the primordial harmony of the landscape, the shorebird species evolutionarily adapted to a particular time and place, arrive.

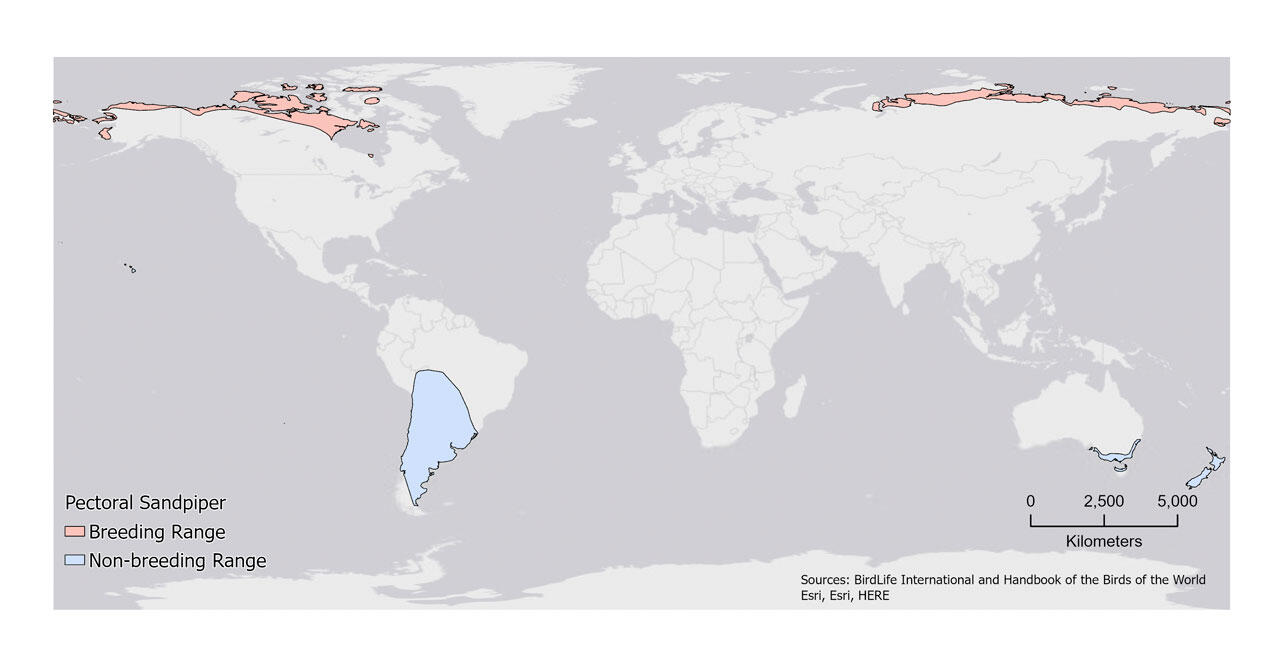

The Pectoral Sandpiper leaves its wintering grounds in southern South America with most flying briskly to the Gulf Coast, up through the center of the United States and Canada, and arriving on the arctic coastal tundra in late May or early June.

On their flight north, Pectoral Sandpipers fly and fly and fly and fly and fly with determined destination in every flap of their wings. Much of the territory beneath the flight path is land abustle with other shorebirds, previously arrived, already going about their courting and nesting rituals.

The typical flattened map of circular Earth shows Pectoral breeding range as a long thin horizontal line stretched from Siberia across far northern North America. A better depiction from a world globe view shows a semi-circular line around the North Pole that follows the narrow arctic coastal plain where land meets ocean, predominantly north of the Arctic Circle.

This is a cold land, dark much of the year with thick continuous permafrost and a mean daily maximum temperature in summer reaching only 46 degrees Fahrenheit. The Pectoral’s nest is typically found on relatively flat and marshy tundra with sedges and grasses. When snow cover reaches or falls below 30 percent, this sandpiper mats down the grasses and sedges atop a raised ridge or hummock, molding them into a depression or cup in which she lays the eggs. The nest is lined with plants available in the landscape that provide better insulation from the cold and dampness—sort of a GORE-TEX lining to protect the eggs and young. Nest concealment increases as the adjacent vegetation slowly grows, creeping and encroaching into the space surrounding the nest.

Pectoral Sandpiper as a breeding bird residing in this harsh, chilly, energy-demanding climate faces the daunting task of balancing energy required to keep the eggs heated with time away from the nest foraging for her own survival. Only the female incubates, leaving the nest only for short periods to feed. The male takes no part.

Residence on breeding grounds is fleeting, and before long the master of migration once again resumes its migratory motion.

Adult Pectorals on their southern migration once again pass through central Canada and United States. The later-migrating juveniles disperse more widely across the continent. Pectoral Sandpipers are uncommon fall migrants at Great Salt Lake, mostly juveniles occurring singly or in small flocks rarely exceeding more than 50 birds. Fall counts greatly outnumber spring counts, as this species’ occurrence in spring is extremely rare.

Individual feathers on the back and wings of many shorebirds are works of still life art, painted from nature’s palette into images with tints of color, shape, and pattern. The feathers of a freshly molted juvenile Pectoral Sandpiper defy the notion of subtlety characteristic of much of shorebird beauty. The juvenile Pectoral Sandpiper is adorned with feathers of black or dark brown interiors divided by a dark center line, fringed crisply and exquisitely with chestnut, buff, and white markings. Here on the upperparts of a young Pectoral Sandpiper lies classical colorful beauty to which few humans are immune.

The Pectoral Sandpiper is sometimes referred to as a grasspiper.

And what is a grasspiper?

If you query the online Webster’s Dictionary, you’re told “The word you've entered isn't in the dictionary,” followed by a list of suggestions from grass pea to grass pickerel. Search engines don’t recognize grasspiper as a legitimate word and the familiar wavy red underline appears with questions like “Did you mean grasshopper?” or statements like “including results for grasshopper”.

Local birders were also stumped.

The following survey was sent to a dozen top Utah birders and wetland managers.

Please answer yes or no to each

Do you know what a ___ is?

Grasshopper

Sandpiper

Grasspiper

The unanimous response: YES, YES, NO

Sandpipers and other shorebirds are loosely thought of as birds with long legs and thin bills that go their way picking and probing in the mud or sand often near the sea. What nature separates, an undiscriminating human mind often fails to discern, obscuring finer distinctions and lumping the dissimilar together.

There are sandpipers and other shorebirds that rarely occur on sandy tidal flats or unvegetated mudflats. While not a widely familiar or well-defined term, “grasspiper” floats around and refers to those sandpipers and plovers that frequent grassy or other vegetated sites, sometimes but not always amid pools or ponds of water. These include species like Upland, Buff-breasted, Solitary and Baird’s Sandpipers, and American Golden Plover. From its arctic tundra nesting ground of grass and sedges, along its migratory path of flooded grasslands, pastures, rice fields, sod farms, and grass-bordered lagoons, to the grasslands and marshy areas of southern South America, Pectoral Sandpiper is much less a sandpiper than a grasspiper!

A piper is one that plays the pipes, like a bagpiper. Sandpipers and grasspipers, when stopping at critical fueling spots like Great Salt Lake, are motion supreme as they pick and probe for insects or wheel about the sky, all the while projecting their whistled and short piped calls, adding their voices to the musical chorus of the landscape.

We would like to thank Richard Holmes, Mike Malmquist, Ann Neville, John Neill, Jennifer Speers, Heather Dove, Brian Tavernia, and Marcelle Shoop for reviewing and making helpful comments.