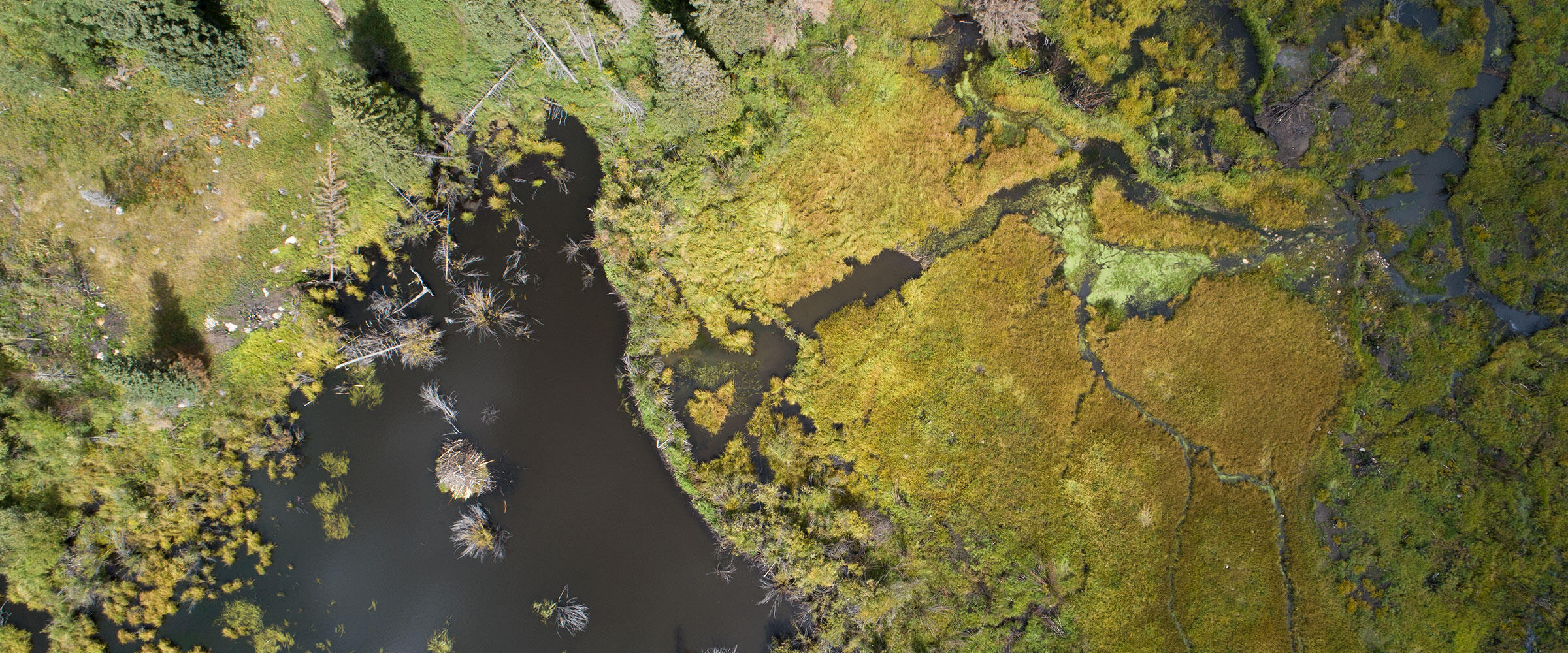

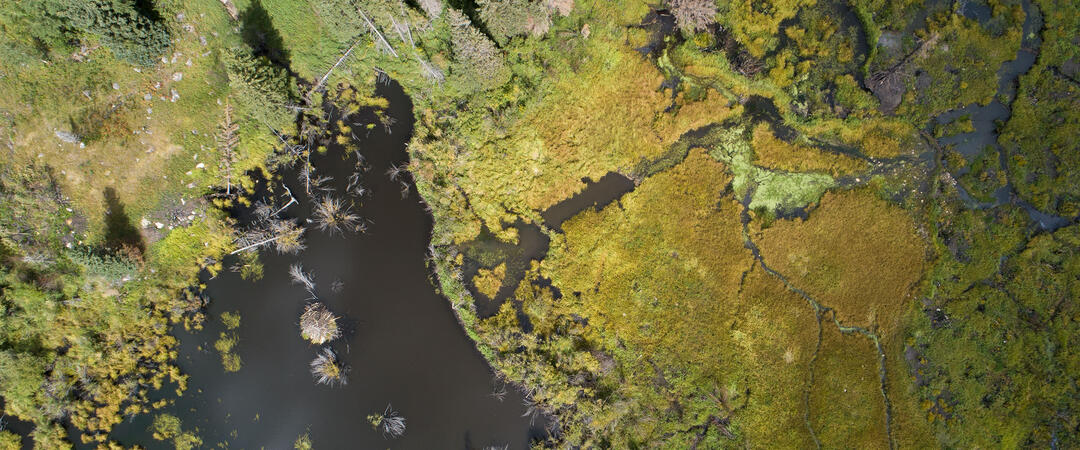

Colorado and the West face unprecedented drought conditions, impacts from wildfires, and water scarcity driven by climate change. These changes threaten our local and regional water supplies, our food supply, bird habitat, economies, and our quality of life. Beavers can help mitigate these impacts. Beavers re-shape the landscapes where they live, creating wet meadow complexes in an otherwise dry area. These diverse wetlands provide important habitat for birds and other wildlife. Beaver wetlands even survived Colorado’s largest wildfire, the Cameron Peak Fire, and continue to provide critical water quality and wildlife habitat functions, a weighty win-win.

To learn more, Audubon Rockies staff went into the Poudre Canyon to capture images of the stark, burnt landscape surrounding vibrant green vegetation and clear flowing water at the Cameron Peak burn scar. We also caught up with an ecohydrologist and researcher who specializes in beavers, Dr. Emily Fairfax, to ask questions about the resilience and benefits of beaver complexes. Here’s what we learned.

Watersheds are our primary water infrastructure. How do beaver wetlands help watersheds and water supplies be more resilient to and recover from wildfire?

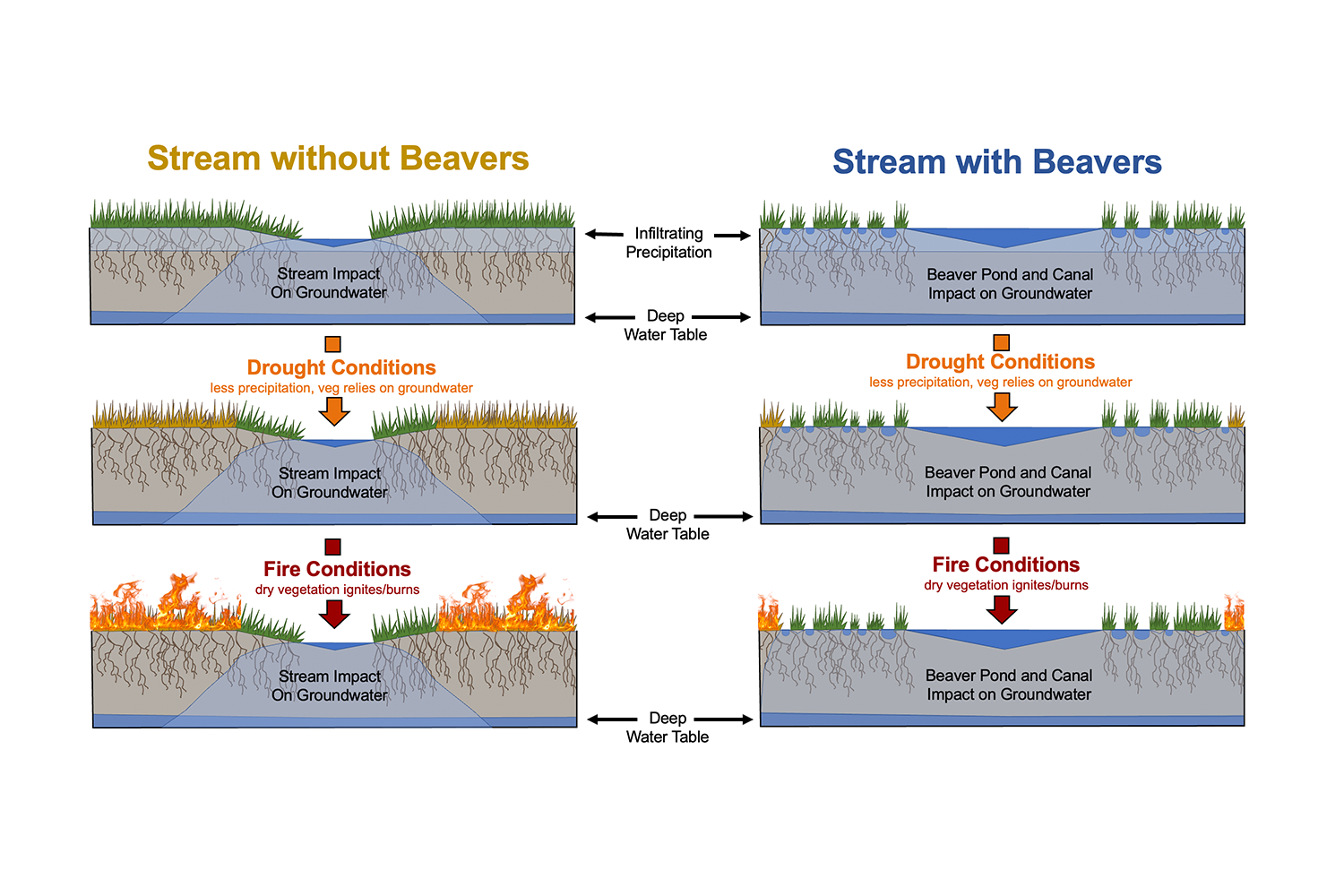

Beaver wetlands can store an enormous amount of water on the landscape—both in the surface water ponds and canals as well as underground in the soil that surrounds them. These wetlands accumulate water during wetter periods when there is a lot of precipitation or runoff. Then when it’s dry and the incoming water supply is “cut off”, the water stored in beaver complexes is still accessible to nearby plant roots, keeping them green and lush. Plants become particularly dangerous fire fuels when they’re dry, but the plants in beaver complexes are well-watered so they’re much less flammable than the surrounding areas. It’s like trying to start a campfire: you want to gather the driest materials possible; you don’t go and gather a bunch of wet leaves.

How do beaver wetlands support ecological services directly related to rivers and water supply downstream?

Beavers have three main impacts on river water: they slow it, spread it, and store it. Importantly, they do not stop water altogether. Historically there were a lot more wetlands throughout the American West than what we see today, including many more beaver wetlands. So when we think about beavers changing how and when water is delivered downstream, it’s important to remember that we’re currently in the altered flow regime and adding wetlands nudges the riverscapes back towards a more natural and resilient state.

One or two beaver wetlands might not make a big difference in how and when a river flows. Yet there are many examples—especially in the Rocky Mountains—of 10’s to 100’s of beaver complexes, one after another, fundamentally changing the flow regime of a river or stream. The more beaver complexes you have, the larger their effect will be. In many places, snow has the primary job of slowing and storing water. But as the climate continues to change and precipitation shifts from snow-dominant to rain-dominant in parts of the West, something else is going to need to start slowing and storing water so that it’s available in the summer when plants need it. Beaver wetlands are one thing that can help do that.

As climate change reshapes our water supply availability through deep periods of drought and intense localized storms, how are beaver wetlands able to help?

Beaver wetlands are very complex, broad landscape features. Their resilience to droughts and floods and fires all go hand-in-hand. When a flood wave travels down a narrow, confined stream channel, it has a lot of power, moves quickly, and can be really destructive. But when it hits a beaver wetland, the flood wave is routed in the broad pond and along the canals. This causes it to physically spread out over the entire floodplain and gives water time to sink into the soil. The volume of water is the same in both situations, but when it’s spread out by the beaver wetland it loses power and some of it is stored locally instead of all the water just ripping downstream. Then when you do have a deep, prolonged drought, enough water has been stored in the beaver wetland and surrounding soil to sustain the ecosystem and keep habitat intact.

Can you describe how beaver wetlands sustain key habitat for birds and other wildlife?

Beavers do an outstanding job of both creating and maintaining stable, highly biodiverse habitat. They are incredibly resistant to disturbance, and that makes them an attractive place to call home for many different animal species. If you live in or around the beaver wetland, your home is less likely to wash away, dry out, or burn. And if you’re a species that needs reliable water, that is getting increasingly rare in the West. But it’s abundant in beaver wetlands. Beavers also create a mosaic of water temperatures, water depths, shading, and land covers by simply going about their daily lives chewing trees, digging canals, and building dams. They can transform even heavily degraded, simple streams into complex, heterogeneous wetlands capable of supporting a vast array of plants and animals with differing ecological needs. The beavers are doing it to ensure their own survival, but the secondary benefits for other species cannot be overstated.

Is there anything else you would like to add on the importance of beavers and their wetlands now and into the future?

Beavers and humans coexisted for thousands and thousands of years prior to the European-North American fur trade. Many Indigenous people on this continent know how important beavers are for creating and maintaining wetland habitat. I’m optimistic for beavers and their wetlands in the future; more and more people are getting interested and involved in beaver-based restoration and conservation every day. I just want people to remember that listening—not just to statistics and model outputs, but also to people and stories—is probably the fastest and most successful path forward.

All of us depend on natural systems for clean and reliable water. Beavers and the diverse habitat they support can be a key Western water security strategy—for people, birds, and other wildlife. Models show that climate change and historic drought will continue to affect the Colorado River Basin and further increase the severity and frequency of wildfires. These fires are devastating to communities, wildlife, and Colorado’s rivers and waterways. In the wake of Colorado’s three historic wildfires in 2020 and future wildfires, beaver activity and wetlands, and beaver mimicry low-tech process-based restoration techniques can help reduce the impacts of wildfires on water supplies and assist in wildfire recovery by sustaining wet-meadow and riverscape plant communities.