Several months ago, the National Audubon Society solicited article pitches about unsung heroes of the bird world. That got me thinking about who would be considered an unsung hero in my neck of the woods. I asked Mary Harris—president of the Roaring Fork Audubon and my birding mentor—if she knew anyone who fit the bill; and, without a moment’s hesitation, she said, “Delia Malone.”

For as long as Delia “Dee” Malone can remember, she was interested in the great outdoors. When she was only 12 years old, she climbed the tallest peak in the lower 48, California’s Mount Whitney. So it seems only natural that she followed her passion down a career path in education and ecology.

Along that path, Dee met John Emerick, ecologist and professor emeritus at the Department of Environmental Science and Engineering at the Colorado School of Mines. It was the mid-1980s, and she was in one of the mountain ecology seminars he taught for the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies (ACES). Fast forward to the late 1990s, when Dee and John began a professional and personal partnership.

Dee’s most rewarding birding experience occurred in 2000 with several women birder friends. Their surveys of breeding birds, vegetation, small mammals, and mesopredators convinced Pitkin County to protect North Star Nature Preserve for wildlife. Of special concern was safeguarding a Great Blue Heron rookery from rampant recreational disturbance. Thanks to the breeding bird surveys, the preserve was designated as one of National Audubon’s “Important Bird Areas.” Way to go, ladies!

In 2001, John joined Dee in conducting bird surveys in the preserve and Hunter Creek near Aspen. They also studied the environmental impacts of the Rio Grande and Government Trails on bird and small animal activity. The latter project became the subject for Dee’s M.S. in Environmental Sciences, which she received in 2002 from the University of Colorado in Denver.

From 2003-2005, Dee conducted virtually all the fieldwork for the Roaring Fork Stream Health Initiative, determining the condition of in-stream and riparian habitats along the Roaring Fork River and its major tributaries. An important part of that study entailed an assessment of bird communities, including American Dippers along the Fryingpan River.

“Dee is fueled by her passion for birds, wildlife, and conservation of natural habitats,” says John, “and her interest in a multitude of factors that support healthy bird populations.” According to John, Dee is an ecologist with more of a big-picture perspective on environmental issues than that of other advocates. If she’s asked why the Greater Sage-Grouse deserves protection, she discusses a host of scientific reasons, John says, that go well beyond an explanation of the imperiled status of the species.

Dee mentored Mary Harris on one of Mary’s most rewarding journeys: learning the secret of bird song. “Not only is it thoroughly interesting and educational to be around Dee,” says Mary, “but it is extremely inspirational as well.”

Mary admires Dee for writing letters in response to every conservation action that comes Dee’s way. Her letters, Mary says, are powerful testaments to the years of knowledge and experience that back up every point Dee makes. Dee’s list of publications is impressive and she gives many local and statewide presentations. Her colleagues admire her ability to respond to challenging questions without ruffled feathers.

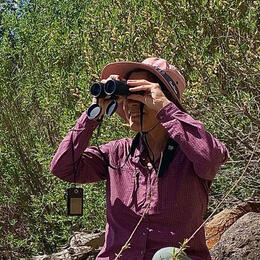

As if all these accomplishments weren’t enough, Dee has worked with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program for more than a decade, conducting rare plant, bird, and wildlife surveys throughout Colorado. She’s also a member of the executive committee of the Sierra Club’s Colorado chapter and serves as its wildlife chair. In her role as vice-chair of the Roaring Fork Audubon board, one of the things she enjoys is connecting people to nature by leading educational walks.

One such long, but easy, walk for older adults was in Moab, Utah. “Everyone was happy for the first five miles,” remembers Dee. “Then hunger and thirst and vocalized thoughts of ‘are we lost?’ set in.” The group appeared dead tired. That’s when the Turkey Vultures showed up. Although Dee assured the group that the birds were scavengers, the birds’ presence gave the group the impetus it needed to push for the last mile.

Dee considers habitat alteration and fragmentation, caused by climate change and human activities, the two most important causes for the decline of birds. Some easy actions she recommends are putting in native plants and not using chemicals that kill the insects that birds consume. “To provide natural resources for birds can make an important difference in the survival of an individual bird,” Dee says. She adds, “When individuals survive, populations do better, and when populations do better, that's when we are protecting the species.”

Through her professional and volunteer efforts, Dee gives her all to protect the inhabitants of the Colorado landscape that she so loves and calls home. She earns my vote hands down as an unsung hero for birds.